Posted 6 August 2022

I have been been doing 3D printing (a ‘Maker’ in modern jargon) for almost a decade now, and almost all my designs started out life in TinkerCad – Autodesk’s wonderful online 3D design tool. As I mentioned in my 2014 post comparing AutoDesk’s TinkerCad and 123d Design offerings, TinkerCad is simple and easy to use, powerful due to its large suite of primitive 3D objects and manipulation features, but runs out of gas when dealing with rounded corners, internal fillets, arbitrary chamfers and other sophisticated mesh manipulation options.

Consequently, I have been keeping an eye out for more modern alternatives to TinkerCad – something with the horsepower to do more sophisticated mesh modeling, but still simple enough for an old broke-down engineer to learn in the finite amount of time I have left on earth. As I discovered eight years ago, AutoDesk’s 123D Design offering wasn’t the app I was looking for, but Blender, with the newly introduced CAD Sketcher and CAD Transforms add-ins, may well be. Blender seems to be aimed more at graphic artists, animators, and 3D world-builders rather than for the kind of dimension-driven precision design for 3D printing, but the CAD Sketcher and CAD Transforms add-ons go a long way toward providing explicit dimension-driven precision 3D design tools for us maker types.

I ran across the Blender app several months ago and started looking for online tutorials; the first one I found was the famous ‘Donut Tutorial’ by Blender Guru. After several tries and a large amount of frustration due to the radical GUI changes between Blender 2.x and 3.x, I was able to get most of the way through to making a donut. Unfortunately for me, the donut tutorial didn’t really address dimension-driven 3D models at all, so while the tutorial was kinda fun, it didn’t really address my issue. Then I ran across Maker Tales Jonathan Kobylanski’s demo of the CAD Sketcher V0.24 Blender add-on, and I became convinced that Blender might well be a viable TinkerCad replacment.

So, I worked my way through Jonathan’s CAD Sketcher 0.24 tutorial, and as usual got in trouble several times due to my ignorance of basic Blender GUI techniques. After posting about my problems, Jonathan was kind enough to point me at his paid “How To Use Blender For 3D Printing” 10-lesson series for $124USD. I signed right up, and so far have worked (and I do mean worked!) my way through the first six lessons. I have to say this may be the best money I’ve ever spent on self-education (and at my advanced age, that is saying a LOT 🙂 ). In particular, Jonathan starts off with the assumption that the student knows absolutely NOTHING about Blender (which was certainly true in my case) and shows how to set the program up with precision 3D modeling in mind. All lessons are extensively documented, with video, audio, and all keypresses fully described. At first I was more than a little intimidated by the deluge of short-cut keys (and still am a little bit), but Jonathan’s lessons expose the viewer to slightly more bite-size chunks than the normal fire-hose method, so I was able to stay more or less on the same continent with him as he moved through the design step. I also found it extremely helpful to go back through the first few lessons several times (very easy to do with the academy.makertales.com lesson layout), even to the point of playing and replaying particular steps until I was comfortable with whatever procedure was being taught. There is a MakerTales Discord server and a channel dedicated to helping academy students, and Jonathan seems to be pretty responsive in responding to my (usually clueless) comments and pleas for help.

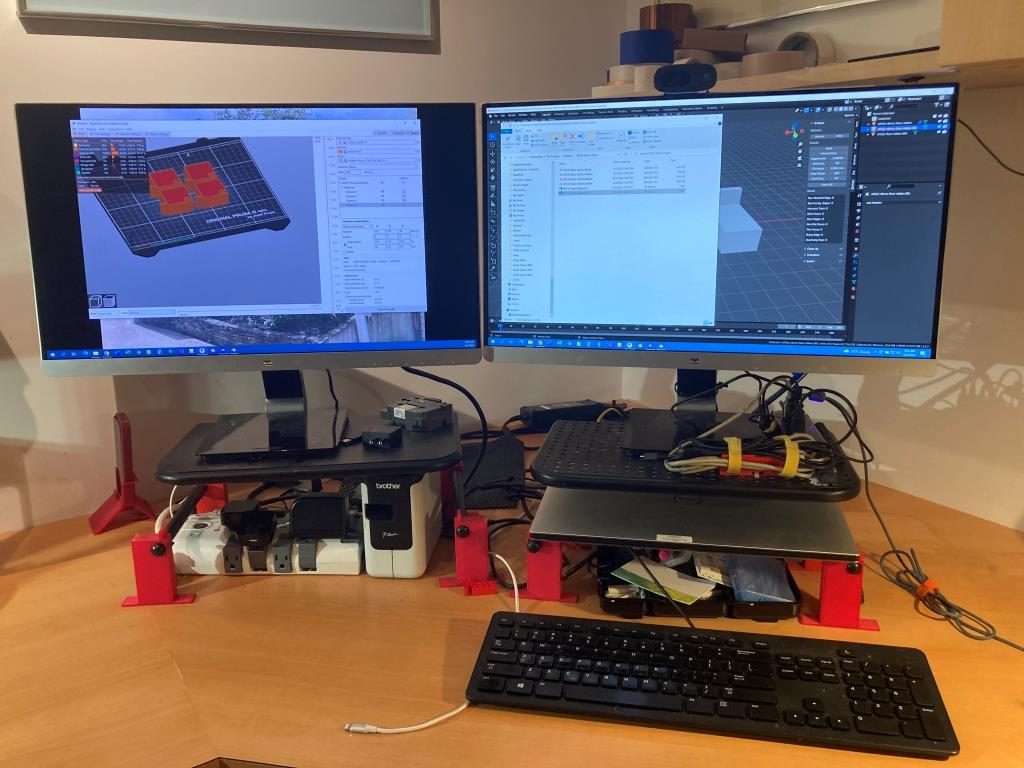

Jonathan encourages his students to go beyond the lessons and to modify or extend the particular focus of any lesson, so I decided to try and use Blender/CAD Sketcher for a small project I have been considering. My main PC is a Dell XPS15 laptop, connected to two 24″ monitors via a Dell WD19TBS Thunderbolt docking station. I have the monitors on 4″ risers, but found they still weren’t high enough for comfortable viewing and seating ergonomics, so I designed (in TCAD, several years ago) a set of riser risers as shown in the image below

As shown above, the ‘riser elevator design incorporates a built-in shelf for my XPS15 laptop. This has worked well for years, but recently I have been looking for ways to simplify/neaten up my workspace. I found that I could move my junk tray from the side of my work area to the currently unused space underneath my laptop, but with the current arrangement there isn’t enough clearance above the tray to see/access the stuff in the back. I was originally thinking of simply replacing the current 3D printed risers with new ones 40mm higher, but in an ‘aha!’ moment I realized I didn’t have to replace the risers – I could simply add another riser on top. The new piece would mate with the current riser vertical tab that keeps the laptop from sliding sideways, and then replicate the same vertical tab, but 40mm higher.

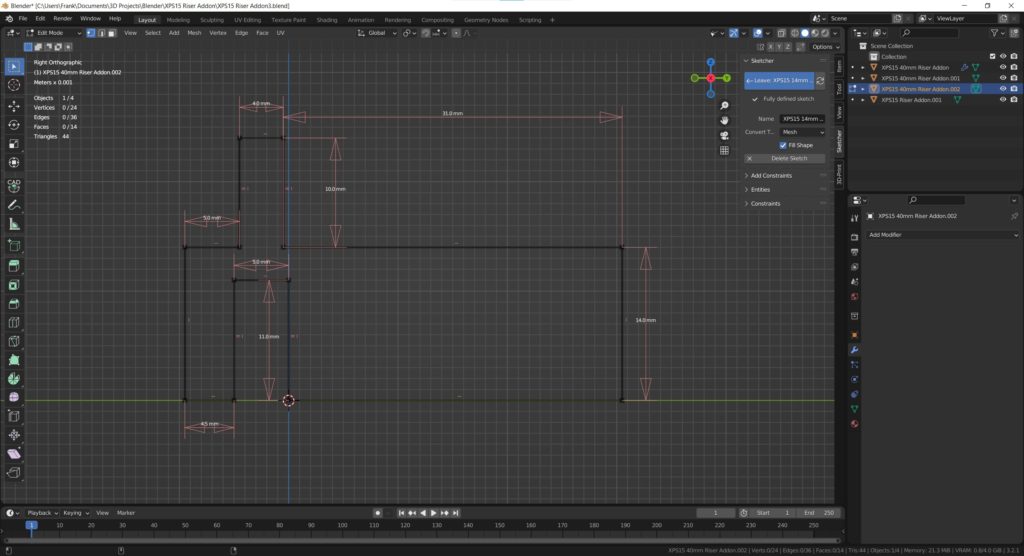

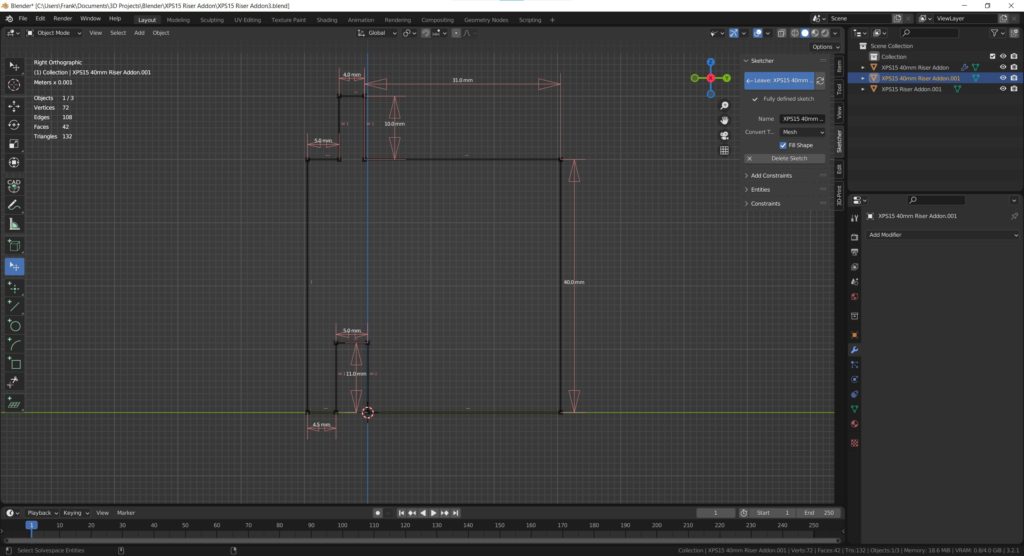

Doing either the re-designed riser or the add-on would be trivial in TinkerCad, but I thought it would be a good project to try in Blender, now that I have some small inkling of what I’m doing there. So, after the normal number of screwups, I came up with a fully-defined sketch for a small test piece (I fully subscribe to Jonathan’s “When in doubt – test it out” philosophy), as shown:

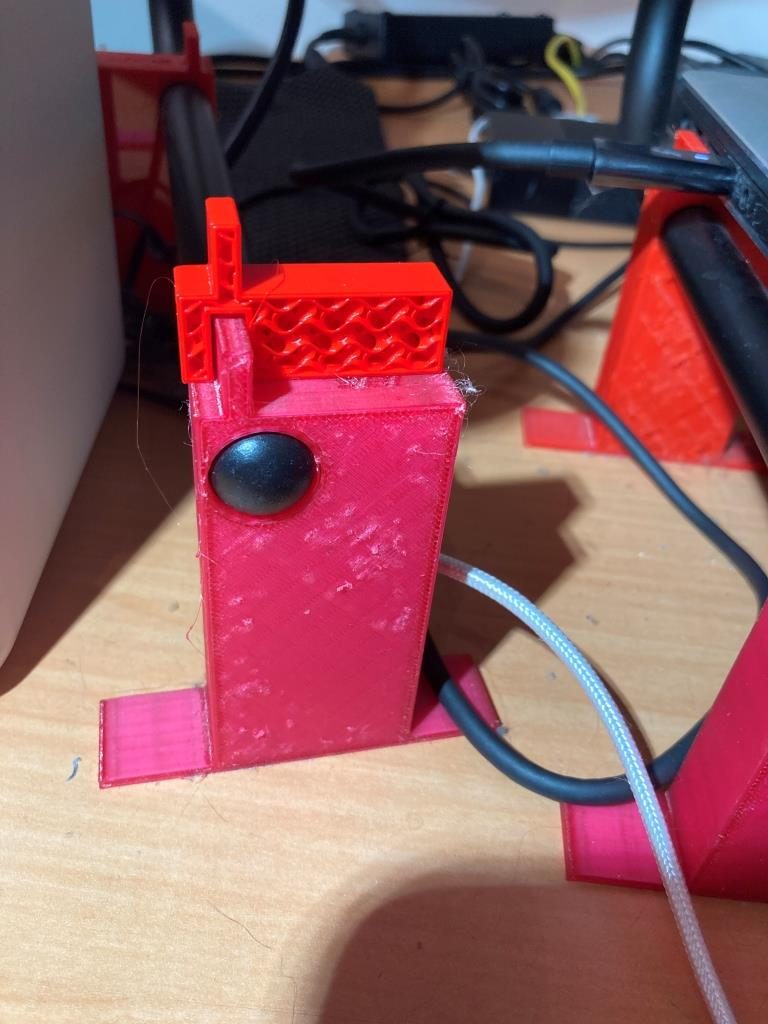

I then 3D printed on my Prusa MK3S printer. Halfway through the print job I realized I didn’t need the full 20mm thickness to test the geometry, so I stopped it midway through and placed it on top of one of the original risers, as shown in the following photo:

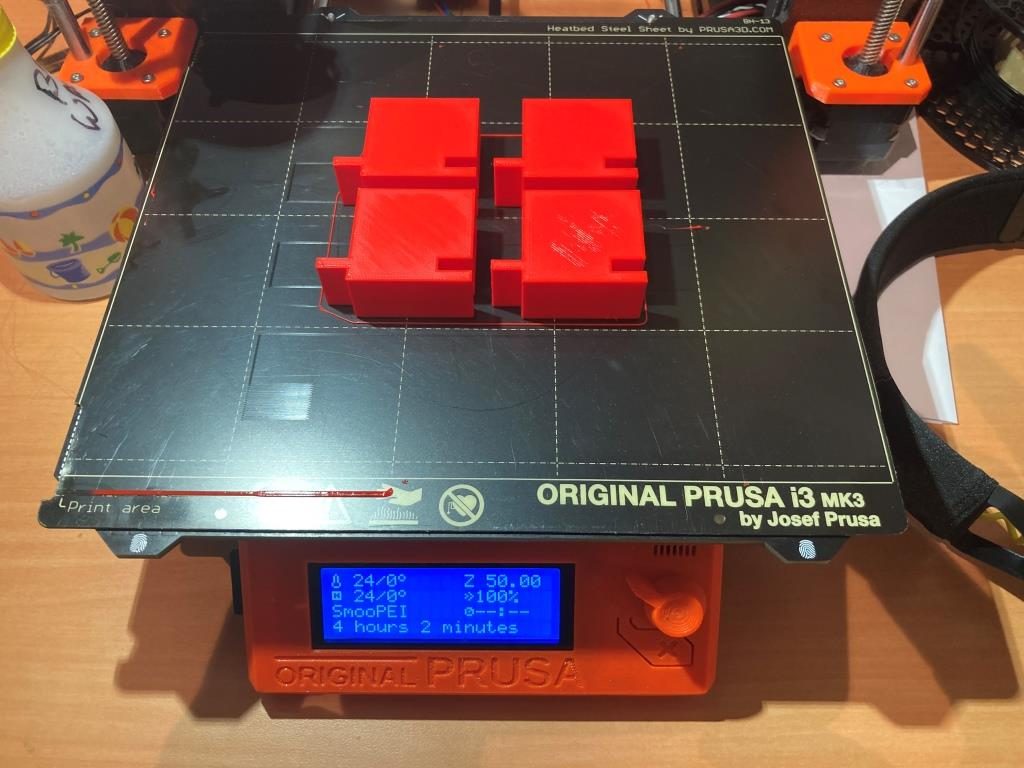

After convincing myself that the design was going to work, I modified the sketch for the full 40mm height I wanted, and printed 4ea out, as shown:

After installation, I now have my laptop higher by 40mm, and better/easier access to my junk tray as shown – success!

And more than that, I have now developed enough confidence in Blender/CAD Sketcher to move my 3D print designs there rather than relying strictly on TinkerCad. Thanks Jonathan!

16 August 2022 Update:

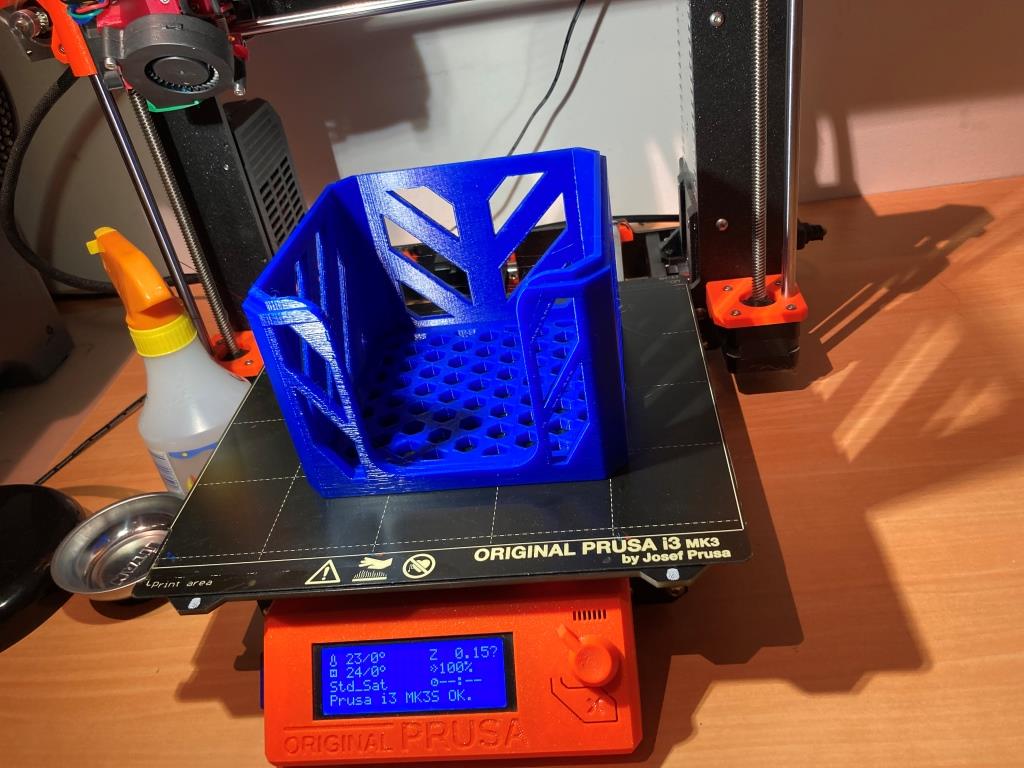

Just finished Learning Project 7: Stackable Storage Crate, and my brain is bulging at the seams – whew! After finishing, I just had to try printing one (or two, if I want to see whether or not I really got the nesting geometry right), even though each print is something over 13 hours on my Prusa MK3S with a 0.6mm nozzle. Here’s the result:

Frank